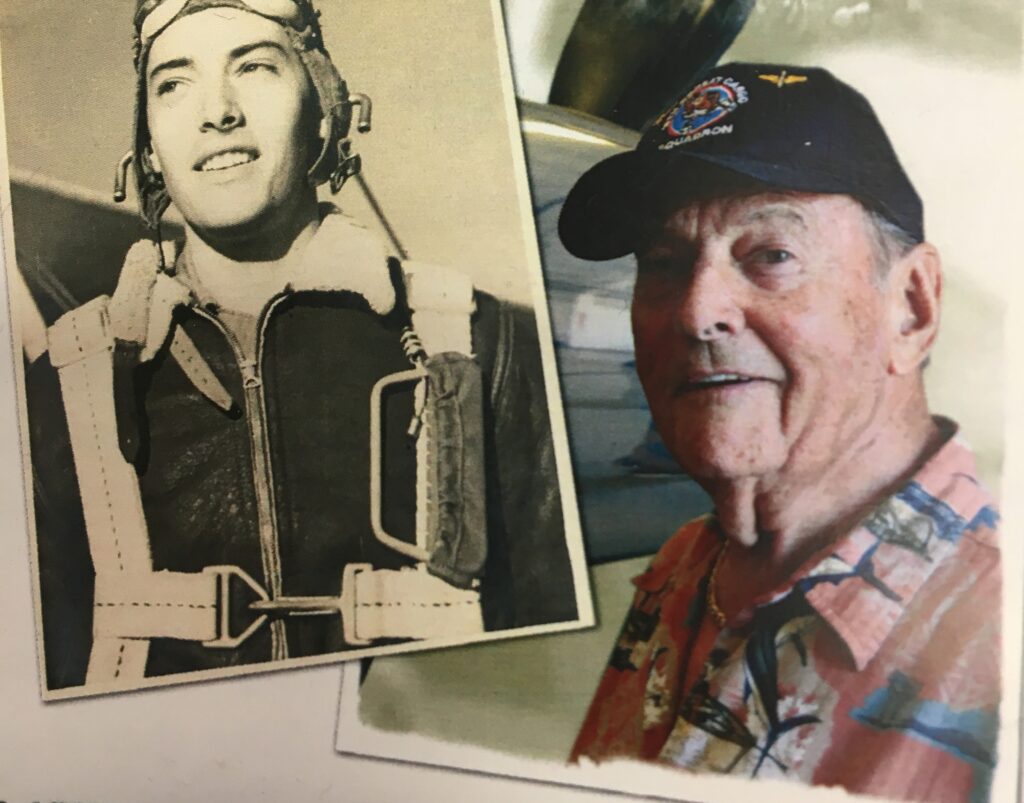

Ninety-year-old Walter Lawrence dodged his share of bullets and hockey pucks in his younger years. These days, he’s steering clear of potholes in the scenic roads he likes to travel on his bicycle—and the advantages of “really aggressive windows” in his retirement community.

A tough and wiry hockey player before the war, Lawrence started his career in the Army in ROTC at Clarkson Tech in Potsdam, New York. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor occurred during his freshman year, and he and fellow officers were issued orders to report to Syracuse Army Air Force Base after the first year of America’s involvement in the Second World War. From Syracuse, like so many other servicemen, Lawrence was sent to Biloxi, Mississippi for basic training and a mandatory six-week quarantine.

“At the end of the quarantine, we went into Biloxi to have some fun and found that all of the local businesses—stores and restaurants—has signs posted saying ‘No Servicemen.’ The guys who had been there before had ruined it for us with fighting and causing ruckuses,” Lawrence said.

At the time, Lawrence had only flown as a passenger in a commercial plane. He hadn’t even been in a cockpit, but he was one of the 100 guys selected to proceed to aviation training in Ohio.

“They picked 100 of us to train as pilots and sent us to the University of Toledo. The difference between Biloxi and Toledo was night and day. There hadn’t been any servicemen in Toledo, and [the civilians there] couldn’t do enough for us.”

During the day, the pilots-in-training learned the basics of navigation and weather, and in the evening, they checked the bulletin board in the study hall for the new posts. “The girls, the mothers and the daughters, would put notices on the bulleting board to invite cadets out for horseback riding and this, that and the other. It was a very wealthy area and that was definitely a high point,” he remembered.

[ulp id=’xkA7bnsbSMSAnwAm’]

Lawrence and his classmates earned their wings in May of 1944. After training in Santa Ana, Thunderbird Field and Douglas Army Airfield in Arizona, and Bowman Field in Louisville, Kentucky, Lawrence finally picked up his C-46 and headed for West Palm Beach. Stopping in Ascension Island, Nepal and the Gold Coast of Africa, the squadrons made their way to India and then to Burma.

In Burma, the pilots stayed in dirt huts with mats covering the floor. The area was known for Malaria, so they put posts on their cots and ensconced themselves in mosquito netting. Their base was near the Irrawaddy River, and native women washed their uniforms in the water and laid them out to dry on the rocks.

“The British had quite a few Spitfires over there, and they were fighting the Japs all the way from Mandalay down to Rangoon. We supplied everything that they needed in support of those missions. Sometimes we landed and sometimes we dropped supplies attached to parachutes. We transported metal for landing strips in the jungle, bulldozers, all their food, fuel, and everything they needed,” Lawrence explained.

“There were no inland routes to deliver supplies, so we had to provide a significant amount of air support. We had four squadrons with 25 planes each stationed in different areas. Each of those C-46s could carry 12 tons of cargo. We had two Pratt & Whitney 2800s on there, which were terrific for short-field takeoffs and landings.”

Between campaigns, the British socialized with the Americans who were stationed in Burma. “We were always having tea with them. It was a ritual when we landed,” he said. “The Brits had it tough, though, because they always had to be alert for the Japs, who would make a stand and try to come back.

“Once when we were off loading an aircraft, the local Burmese were hauling all of the supplies when the Japanese came back and started shooting at us. We had three bullet holes in the plane by the cargo door. These guys stopped unloading.

“I don’t know if I should tell you this or not,” he paused, “but we wanted to get the hell out of there, because if they came, they would take the ship or shoot it. We urged the workers to hurry. That particular time, we were carrying a lot of gasoline, which was hard to unload, in addition to the food supplies. Instead of responding to our promptings to hurry, they stopped unloading completely,” he chuckled at the memory. “I had an issued .45 and fired a couple tracer bullets right down close to their feet and flames came our of the ground from the bullets. That got their attention, and they hurried to unload the rest of the cargo.

“As the British were pushing the Japs down, they captured a lot of equipment. Then they sold it for a carton of cigarettes or a bottle of vodka,” Lawrence said. “I got a Japanese carbine with a bayonet and an automatic rifle with arms that fold down and a whole box of ammunition. When we were deadheading with empty 55-gallon gasoline drums, we’d push one out of the cargo door into some isolated river and then we’d circle around and take turns shooting at it. Maybe I shouldn’t have told you that either,” he winked.

One of Lawrence’s most emotional memories of the war was in volunteering for a mission toward the end of the conflict retrieving POWs who were in bad shape and being released because they needed hospitalization. He and his co-pilot delivered the wounded soldiers to Calcutta.

When he returned from war, Lawrence was signed by a semi-pro hockey team. He also was director of the youth hockey league in White Plains for 14 years. Not surprisingly, his love for hockey also led him to his wife, who was the ice queen of his college hockey team. They had six children and were married for 45 years before she died in 1990 of lung cancer.

Since his hockey career was never high paying, Lawrence also worked for Exxon for thirty years as a purchasing agent. He retired in 1986 and moved to Texas in 1997. He enjoys keeping up with his kids and 11 grandkids, a very active social calendar and his love for aviation.