Appearing ostentatious worries some private flyers. We have country singers who buy turboprops so nobody can say they flew in on a private jet. We know light jet owners who don’t want to be seen rolling up in a Gulfstream for fear their clients will use that as a bargaining plea for a lower product or service price.

So, of course, when I chatted with Jean-Noel Robert, the business development director for Airbus Corporate Jets, I brought up this argument. I loved his response. He said if a private jet owner wants to be inconspicuous, he or she should fly something bigger, not smaller.

We were in London at a Corporate Jet Investor conference. “What type of plane did you take here today?” he asked me.

“I flew on British Airways.”

“I know, but on what type of plane?”

“An A380, actually.”

“Exactly,” he grinned. “And if you taxied in on an A320, people would think you flew on an airliner, too, right?” I nodded. “Even if it was an ACJ, with a VIP interior, right?”

He lifted a glass of champagne as he saw the lightbulb click in my facial expression. “Now let’s talk about the costs of ownership.”

Between several espressos with “Johnny Christmas,” and a presentation by Andrew Gough from Boeing Business Jets, I left with a new appreciation for the competitiveness of the commercial-grade “bizliner” in the private flight landscape.

Historical sales figures show that the residual values of bizliners have not dropped as significantly as large-cabin business jets, like Gulfstreams or Globals. Gough explained that one of the biggest reasons BBJs hold value is a lack of availability of new aircraft. Both Boeing and Airbus have order books stretching for years. Their business-jet offerings are slipped in among fleet orders for major airlines. But unlike their general aviation counterparts, if an order is cancelled, the aircraft can just be configured as an airliner, not even forming a blip on production.

“The reason we think inventory and residual values will remain steady is that there’s really a lack of availability of new airplanes from the manufacturers,” Gough said at Corporate Jet Investor London 2018. “From a BBJ perspective, we have one current-generation Boeing Business Jet position left, then we’re in full transition to a BBJ Max, which is sold out until 2022. First available position is 2022, that’s a green airplane, then you’ve got to take it to a completion center, and it’s 2023 before you’re operating the aircraft. For a customer that wants to enter the business airliner space, they’re going to have to come to the pre-owned market to do it. Even if they’ve bought a brand new aircraft from the manufacturer, if they want interim lift, they’re going to have to come to the pre-owned market.”

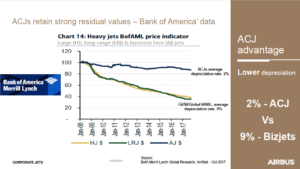

Gough also presented transaction numbers to back his statement up, proving that the asking price of a Global XRS depreciated at an average of nine percent over 10 years. A BBJ, however, depreciated only three percent over 18 years. Jean-Noel presented similar data for the ACJ when compared to a G650 and Global 6000, pictured below.

Lower maintenance costs are a huge reason behind bizliners’ residual value. Gough explained that a CFM56 engine’s on-wing time is 30,000 hours, on average. At 450 hours a year, that’s 66 years before an engine is going in for an off-wing major maintenance event.

Direct operating costs for bizliners are also lower than the average large-cabin business jet. According to ACC, an ACJ319neo will cost 16 percent less annually than a G650ER to operate. Combining those savings with the savings in depreciation, that’s more than $2 million that an owner could potentially save versus a large-cabin business jets.

Charter profits are higher for a bizliner than they are for a traditional business jet, because the market is significantly less competitive, with far fewer FAR Part 121 charter operators than Part 135 operations—and only a handful of bizliners on Part 135 certificates in the U.S.

In addition to their higher residual value, ACJ operators can also switch out fuel tanks and cargo space from one day to the next, allowing them to trade fuel capacity for cargo room, dependent upon the mission at hand. Not to mention, with a range of about 6,750 nautical miles, the ACJ319neo has better range than a Global 6000 or a G550.

[ulp id=’ksrvpykbSKmvluGu’]

Yet another advantage of owning an ACJ is that there are close to 9,000 Airbuses currently in operation, compared to less than 900 Globals, and each one of them has a nearly identical cockpit, meaning there are a whole lot more Airbus-rated pilots, making it easier to find an experienced one.

Of course, bizliners’ biggest draw is sheer cabin size, and although a newer business jet will come equipped with newer cabin technology, an older bizliner can be customized with the same technology for a price. The size of bizliners allows operators to include queen-sized beds, first-class pods, conference rooms, and more.

While you may think that would lead to more expensive hangar costs, that’s not usually the case. Bizliners typically occupy the same ground space as a large-cabin business jet. In fact, the Global 7000 is longer than the ACJ318 and ACJ319. Owners get the same footprint, but up to three times the cabin space, allowing you to sleep your entire immediate family with individual beds. No need to negotiate who gets the private room, and no more sharing private space with your crew.

Pingback: Convair 990 Coronado: Too Fast Too Soon | International Aviation HQ